Active mobility matters!

While cycling and walking were seen as insignificant modes of transport in the past, there is now a rising interest in establishing conditions that actively promote them. This shift is necessary for the benefits it brings to our cities, local economy, physical health, and the general environment.

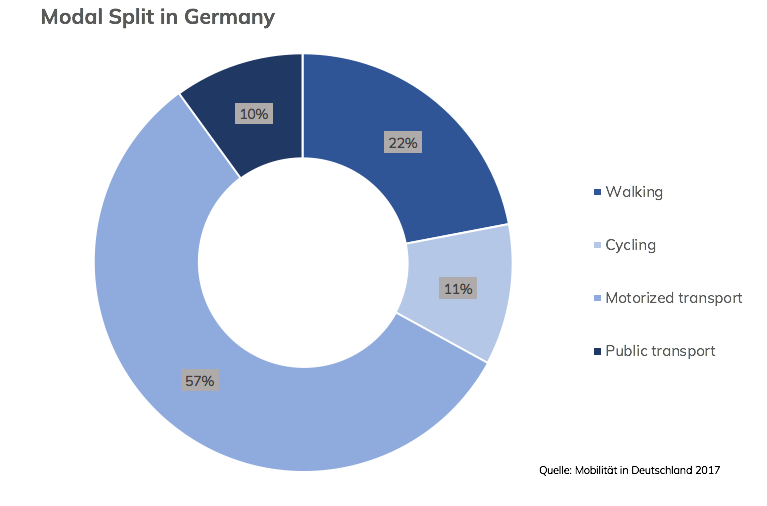

Active mobility takes a large share of daily transport activities already. Just like in many other countries walking and cycling play a vital role in everyday mobility in Germany (see: Modal split in different cities worldwide). In addition, walking and cycling play the crucial role of acting as feeders for public transport systems. In many cities and municipalities across the world, pedestrians and cyclists take a larger share of transportation modes in use. However there is a lot of potential to further increase their share and as a consequence, harvest the wide range of positive impacts more extensively.

Good conditions for active transport are generally a result of good planning strategies however, planning for walking and cycling can be more complicated than expected. Besides an attractive infrastructure, a safe environment and a strong active mobility culture are also important to provide close destinations. This underlines the fact that fostering walking and cycling cannot solely be achieved by infrastructural projects but further requires an integrated approach of urban and transport planning.

Modelling active mobility

Transport and the urban sectors are two strongly interwoven and complex topics. This is the reason why planners and decision makers very often rely on the assistance of planning and decision support systems. Classical transport models are probably the most prominent representatives but also land-use models and integrated land-use and transport models are among them. They are generally used to assess the effect of large infrastructural or urban development projects.

Despite the ongoing development of the mentioned tools, they are rarely designed to model walking and cycling. The challenge lies in the necessity to model on the neighborhood level and the need to adequately consider small changes in the urban environment and transport network. Accordingly while for instance, predicting the effect of a new road ring into future traffic volumes might be possible, the effect of a new pedestrian bridge could be hardly quantified.

Accessibility concept

The accessibility concept can be seen as a potential remedy for this issue. Unlike transport models accessibility models can be used for all transport modes, scales and in addition can consider the interactions between transport and land-use. The accessibility concept in general is characterized by its high flexibility and extensive scope. Therefore unsurprisingly various definitions are existing in the scientific literature:

’the potential of opportunities for interaction’ (G. Hansen 1959)

‘the extent to which the land use-transport system enables (groups of) individuals or goods to reach activities or destinations by means of a (combination of) transport mode(s)’ (Geurs and Van Eck 2001)

‘the number and diversity of places that can be reached within a given travel time and/or cost’ (Bertolini, LeClercq and Kapoen 2005)

‘an expression of the potential number of relevant activities that are located within acceptable reach of a given place or people in acceptable reach of an activity’ (te Brömmelstroet, Marco et al. 2016)

Unlike transport models accessibility models are showing potentials, for example, “How many additional jobs can be reached with a new transit line?” instead of trying to predict the growth of ridership due to new transit lines.

Accessibility components

With the so called accessibility components (Geurs and van Wee 2004) the accessibility concept can be made concrete. Each component can have an influence on accessibility, thus ideally all four components are considered. The access to supermarkets for instance could be influenced by the number of shops available (land-use), the quality of the transport network (transport), the opening hours of the supermarkets (temporal) and finally by the equity in the population (individual).

Nowadays there are countless ways for measuring accessibility and depending on the purpose, resources and data availability appropriate measures are chosen. Among the most used ones are gravity-based and contour measures. However there are more complex ones such as utility-based measures. Depending on the purpose accessibility can be visualized with isochrones as relative simple catchment areas up to complex indicators based on utility models.

Accessibility tools/instruments

For measuring accessibility, accessibility tools are needed and they are termed as accessibility instruments or simply accessibility tools. Normally these tools are built with Geo Information Systems (GIS) that allow them to process and visualize spatial data. There are existing numerous tools with extremely varying purposes, user-interface, user groups and terms of use. Among them are in-house developments of research groups, open source projects but also proprietary software products. To date, there are only few tools existing that allow for dynamic calculations and ad-hoc scenario building. There are also few tools specialized on active mobility only and open source development. Accordingly there is the necessity to further develop accessibility tools to answer the open challenges.

References

Brömmelstroet, Marco te, Cecília Silva, and Luca Bertolini. 2014. “Assessing Usability of Accessibility Instruments.”

Brömmelstroet, Marco, Curtis, Carey, Larsson, Anders, and Milakis, Dimitris. 2016. “Strengths and Weaknesses of Accessibility Instruments in Planning Practice: Technological Rules Based on Experiential Workshops.”

G. Hansen, Walter. 1959. “How Accessibility Shapes Land Use.”

Geurs, Karst T., and Bert Van Wee. 2004. “Accessibility Evaluation of Land-Use and Transport Strategies: Review and Research Directions.”

Hull, Angela, Cecília Silva, and Luca Bertolini. 2012. “Accessibility Instruments for Planning Practice.”

Litman, Todd. 2011. “Evaluating Accessibility for Transportation Planning.” Victoria, BC: Victoria Transport Policy Institute. Retrieved from http://www.vtpi.org/access.pdf (September 18, 2017)